Angle of Attack: Harnessing Wind for Speed and Control

In sailing, few concepts are as fundamental—and as misunderstood—as the angle of attack (AoA). Mastering it can mean the difference between sailing efficiently with speed and balance or struggling with poor performance and excessive leeway. Whether you’re a racer chasing every fraction of a knot or a cruiser seeking comfort and safety, understanding the angle of attack is key to trimming your sails. Before delving into AoA, I suggest you (re)familiarise yourself with the concept of “Points of Sail” as it will help you understand AoA better.

What Is Angle of Attack?

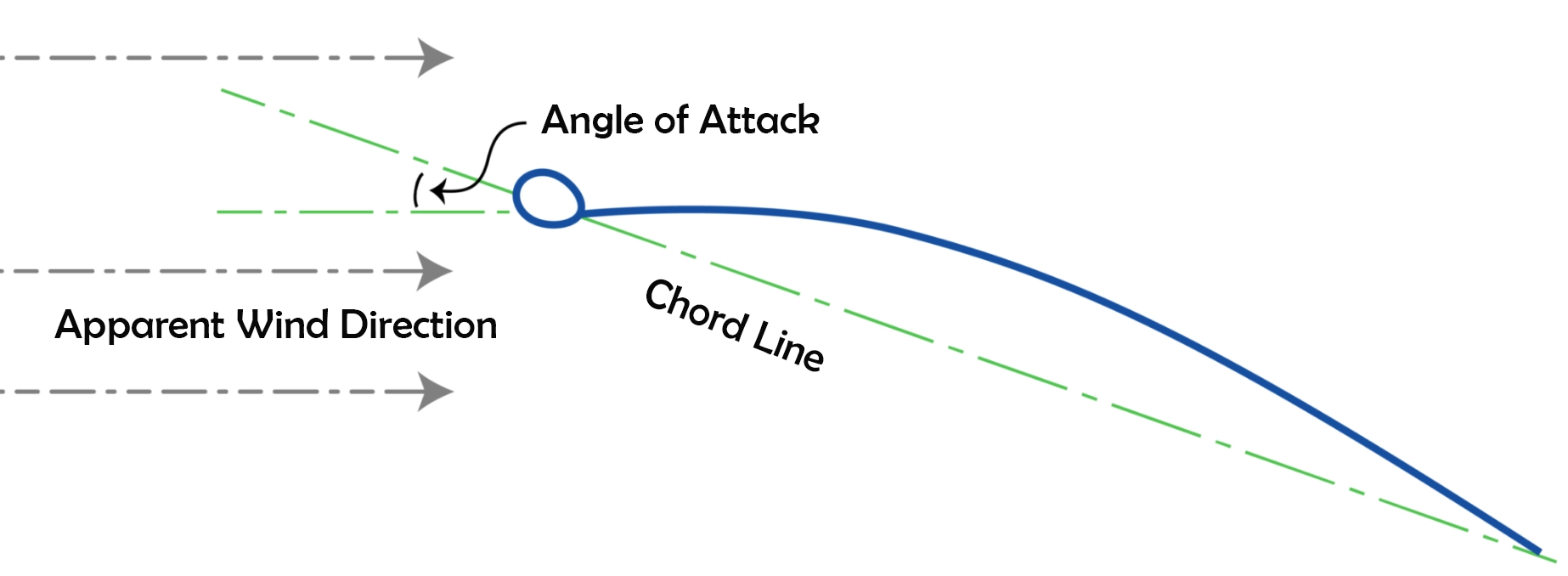

The angle of attack is the angle between:

The chord line of the sail (a straight horizontal line between the luff and leech), and

The apparent wind direction (the wind felt on the boat, which combines true wind and the boat’s motion).

Think of a sail as an aeroplane wing stood on end. The sail generates lift when the angle of attack is set correctly—too little or too much, and performance suffers.

How It Works: Lift and Drag

Correct AoA (efficient lift): The sail deflects airflow smoothly, creating a pressure difference across the two sides of the sail. This produces lift, pulling the boat forward and slightly sideways (countered by the keel or centreboard).

Too small AoA (luffing): The sail stalls at the luff, flapping uselessly. The boat slows.

Too large AoA (stalling): Airflow separates from the leeward side, causing drag and poor lift. The boat heels excessively without gaining speed.

Managing Angle of Attack with Sail Trim

Mainsail

Mainsheet: Primary control—easing decreases AoA, sheeting in increases it.

Traveller: Adjusts boom angle relative to the centerline without radically changing leech tension.

Helm balance: Slight weather helm means the mainsail’s AoA is driving efficiently.

Headsail (Jib/Gen)

Sheet trim: Adjusts AoA relative to the apparent wind.

Jib leads: Indirectly influence AoA by controlling twist and leech tension.

Halyard tension: Doesn’t change AoA directly, but influences entry angle and draft position, which affects how forgiving the AoA is.

Spinnakers

AoA is especially sensitive. Keep the luff on the edge of curling—this ensures maximum projection without collapse.

Angle of Attack and Points of Sail

Close-Hauled: AoA is the smallest (3–5° typical). Trimming precisely is critical; even a slight mis-trim means stalling or luffing.

Reaching: AoA is larger; sails eased for more power, but too much AoA leads to drag.

Running: AoA loses significance; sails act more like drag devices than lift foils, except in apparent-wind-driven planing boats.

Racing Perspective

Racers obsess over the angle of attack because:

Minor adjustments = significant gains. A 2° trim change can mean boat lengths over a leg.

Upwind performance depends on it. The right AoA maximises lift while minimising leeway.

Dynamic trimming: Constant micro-adjustments to keep sails “just on the edge” of luffing ensure peak efficiency.

Racers use telltales (strips of yarn or film on the sail) to monitor AoA:

Inside telltale lifting = sail under-trimmed (sheet in or head up).

Outside telltale lifting = sail over-trimmed (ease sheet or bear away).

Cruising Perspective

Cruisers also benefit from understanding AoA, though priorities differ:

Comfort vs. speed: Cruisers may deliberately sail with a slightly reduced AoA to minimise heel and balance the boat.

Ease of handling: A forgiving AoA setup (flatter sails, eased trim) reduces the need for constant adjustment.

Safety: Avoiding over-trim prevents excessive heel and weather helm, making the boat more stable and comfortable.

Tools for Managing Angle of Attack

Telltales: Best real-time guide; both sides streaming = good trim.

Instruments: Apparent wind angle and boat speed confirm settings.

Feel: Weather helm, heel angle, and acceleration are intuitive cues.

Final Thought

The angle of attack is the heart of sail trim. Get it right, and the sails work like wings, driving the boat efficiently and powerfully. Get it wrong, and even the best sails and rig won’t save you. Racers tune it constantly for maximum speed, while cruisers balance it for comfort and safety. In both cases, the sailor who understands and controls the angle of attack has the wind—and the race—on their side.

Author

-

Rene is a keelboat instructor and sailing coach in the Mandurah area WA. He is also the author of several books about sailing including "The Book of Maritime Idioms" and "Renaming your boat".

View all posts