Why use nautical miles and knots in sailing?

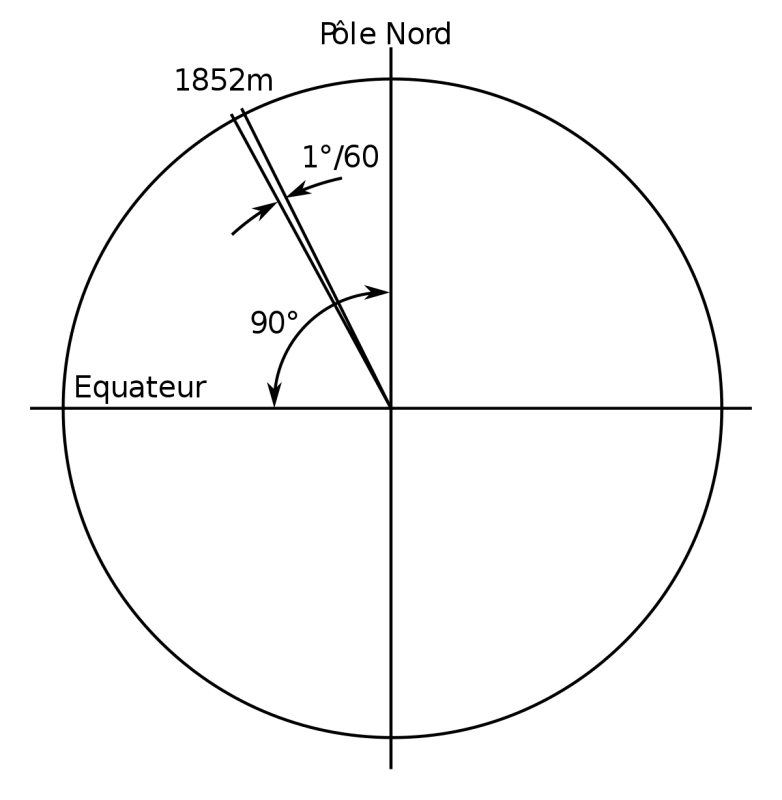

We use nautical miles and knots in sailing because a nautical mile is based on the Earth’s circumference. One nautical mile equals one minute of latitude or 1/60 of a degree. It takes one hour to sail one nautical mile at a speed of one knot. We use nautical miles and knots for navigating and plotting charts.

To better grasp this concept and hone in on the “why,” we need to unpack it a bit and examine the individual components. The collaboration between these components still underpins why we use nautical miles and knots in sailing in today’s digital world rather than kilometres/hour or miles/hour.

- What are nautical miles?

- Why divide the globe up into 360°, minutes and seconds?

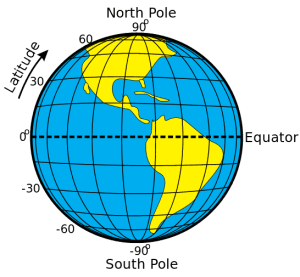

- What is latitude (parallels)?

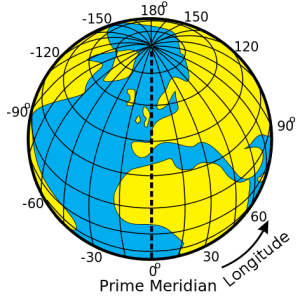

- What is longitude (meridians)?

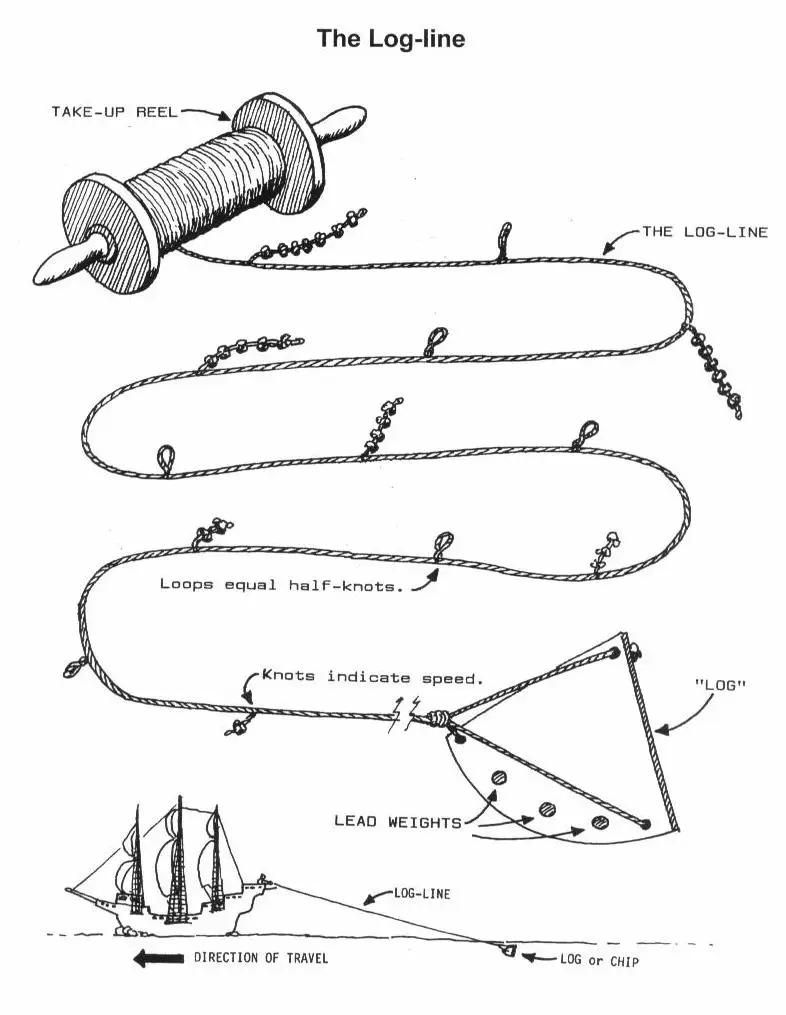

- Why use knots?

1. What is a nautical mile?

1. Relation to the Earth’s Geometry

A nautical mile is based on the geometry of the Earth, specifically its latitude and longitude. One nautical mile is defined as the distance corresponding to one minute of latitude (1/60th of a degree of latitude). Since the Earth is roughly a sphere, this definition ties the unit of distance directly to the planet’s dimensions.

Latitude lines run parallel to the equator, and the distance between each line of latitude is roughly constant, which makes them a good way to measure distance on Earth’s surface.

Because the Earth is about 40,075 kilometres in circumference, the full circle of latitude (360°) is divided into 60 minutes per degree. This gives a nautical mile a value of about 1.852 kilometres or 1.1508 miles.

This definition ensures the nautical mile remains consistent, regardless of your location on the globe.

2. Simplifies Navigation

Since a nautical mile corresponds to one minute of latitude, it’s much easier for navigators to use it in conjunction with their latitude and longitude coordinates when plotting a course.

Latitude is evenly spaced, and each degree of latitude is approximately 60 nautical miles apart. So, if a ship moves one degree north or south, it has travelled roughly 60 nautical miles.

Longitude lines are not evenly spaced (they converge at the poles), but navigators can still use nautical miles for distance calculations based on their position along the globe.

3. Simplifies Calculations at Sea

Sailing and flying long distances often involve plotting courses using charts that are divided into degrees of latitude and longitude. Since nautical miles are tied to these coordinates, they make for an easy conversion between distance and position.

For example, if a ship is travelling from one point to another and needs to know how many nautical miles it has covered, it can directly use the lines of latitude and longitude on the map to calculate the distance. This is much more practical than using miles or kilometres, which don’t have such a direct relationship with the Earth’s grid system.

4. Global Standard

The nautical mile is a global standard used universally in maritime and air navigation, enabling sailors, pilots, and navigators to communicate and operate without confusion, regardless of their location worldwide.

When ships and aircraft use nautical miles, they can rely on a shared understanding of distance, which is essential for international travel, navigation, and safety.

For example, a plane flying over the ocean will use nautical miles for speed and distance, just like a ship does when crossing the seas.

5. Historical Basis

The term “nautical mile” originates from its historical use by sailors and navigators. Before the advent of modern tools like GPS, the relationship between the nautical mile and the Earth’s grid made it the most practical unit of distance for people navigating at sea.

In short, we use nautical miles in sailing because they provide a direct and convenient way to measure distance tied to the Earth’s dimensions, simplify navigation, and ensure global consistency. It’s all about aligning with how we measure the globe itself!

Nautical miles can be abbreviated in several ways, depending on what industry you are from. In sailing terms, we are happy with just “nm”.

2. Why use 360 degrees, minutes and seconds?

1. Why 360°?

The 360° system for measuring angles originated with the ancient Babylonians, one of the earliest civilisations to develop a system of mathematics that could be applied to navigation, astronomy, and timekeeping. Here’s the reasoning behind their choice:

The Babylonians used a base-60 number system (sexagesimal system), which was derived from their observations of the natural world, especially the lunar cycle. They noticed that the Moon’s cycle (from new moon to new moon) took about 29.5 days, which is close to 30. They also saw that the Sun’s path across the sky seemed to be divided into a 360-day year, a rough approximation of the solar year, which contributed to the choice of 360 degrees for a circle.

A circle contains 360 degrees because the ancient Babylonians observed that the number 360 was divisible by many smaller numbers, making it a valuable reference for dividing things like time, space, and angles. It was a practical number that could be easily divided into many smaller units.

Thus, using 360° for a circle became a universal standard in astronomy, navigation, and later in geography. This made it easier to create systems that could divide circles into smaller, measurable units.

2. Why Minutes and Seconds?

Now, for minutes and seconds, we are really talking about how degrees (the 360°) are subdivided:

1 degree (°) is divided into 60 minutes (‘).

1 minute is divided into 60 seconds (“).

This system also comes from the sexagesimal system of the ancient Babylonians, which, as mentioned, was based on 60 as a base number. The reason they used 60 was that 60 is easily divisible by a wide range of smaller numbers (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, etc.), making it a convenient number for dividing a circle or an hour into smaller, more precise parts.

3. Application in Navigation

In navigation and sailing, this system enables precise angular measurement of latitude and longitude, which is crucial for determining a ship’s or aircraft’s position on the globe.

Latitude: Lines of latitude are measured in degrees, and each degree is divided into minutes and seconds. A minute of latitude is approximately 1.85 kilometres (or one nautical mile). This means that sailors or navigators can use this system to determine their latitude, specifically how far north or south they are from the equator.

Longitude: The same system is used for measuring longitude, but here the degrees of longitude can vary in distance depending on where you are on Earth (they converge at the poles). Still, the degree-minute-second system enables precise positioning around the globe.

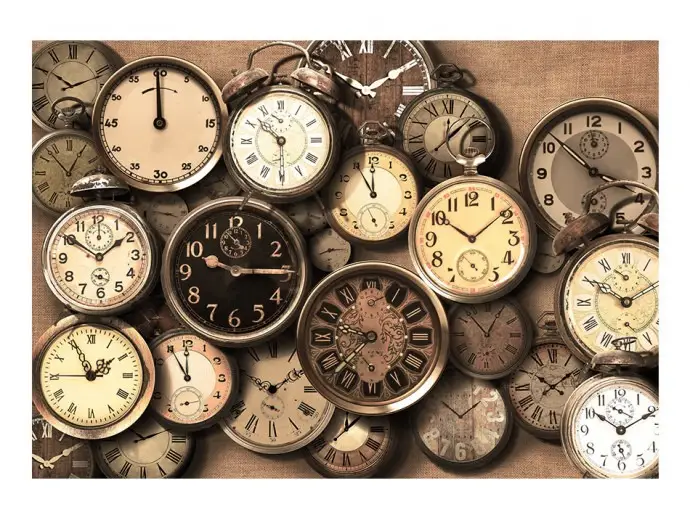

4. Use in Timekeeping

The same system of degrees, minutes, and seconds is applied to time—hence the term “degrees of longitude” is connected to time because the Earth is divided into 24 time zones (one per hour of rotation), and 1 hour corresponds to a 15° shift in longitude.

In sailing and navigation, this is crucial because it helps to link celestial navigation with geographical positions. For example:

Longitude and time are directly linked. Each minute corresponds to 1/60th of a degree of longitude (or 1 minute equals 1 nautical mile of longitude at the equator).

Sailors often use time as a reference point when using instruments like a sextant to determine their position based on the angle between the sun, the horizon, and the ship.

5. Why Keep Using This System?

The 360°, minutes, and seconds system has persisted for centuries for a few key reasons:

Historical Continuity: Once established by ancient astronomers and navigators, the system became deeply entrenched in both maritime and astronomical traditions. Changing this system now would cause massive confusion in global navigation, so it has remained in place for its practicality and consistency.

Precision: It enables precise measurements and adjustments. For instance, with the system of minutes and seconds, you can pinpoint your location with great accuracy, which is essential for modern navigation.

Global Standard: Whether you’re sailing, flying, or using GPS, the system of 360° and its subdivisions is universally recognised and used, ensuring that measurements and coordinates align across the world.

In Summary, the use of 360° for a circle originates from ancient Babylonian astronomy and mathematics, which are based on the lunar year and a base-60 number system.

- Minutes and seconds are subdivisions of degrees, also rooted in the Babylonian system, making it easier to divide and measure circles (or angles) precisely.

- This system became standard in navigation because it provides a precise, consistent method of measuring position using latitude and longitude.

- The system of degrees, minutes, and seconds has been passed down through history because of its practicality, precision, and global consistency.

So, when you’re on the water navigating with charts and GPS, you’re essentially using thousands of years of human astronomy, mathematics, and exploration to make sure you can measure distance, direction, and position accurately!

In practical terms, we write degrees, minutes, and seconds as follows:

For example, 20°46′23.43454″

Note the use of the notation:

- Degree = °

- Minute = ′

- Second = ″

However, to plot points on your chart, you would use degrees and minutes and convert any seconds to a decimal. For example,

Convert 40° 19′ 30″ N

30″ / 60 = 0.5′

Latitude: 40° 19.5′ N

Making a grid…

We all have heard about a “grid reference.” To determine our location on a map or chart, we require a grid system that can pinpoint our position or the location of other objects, allowing us to visualise the relationship between our current location and our desired destination. Having criss-cross lines on a map or chart will do that job nicely if we can understand what these lines are called and the relative distance between them.

Our globe is round(ish) and not a flat map, so we need to adjust it accordingly. How we do this is another story for another time…

So, let’s put some names to these grid lines now…

3. What is meant by latitude?

Think of latitudes as “lines ” that run east to west across the globe, but tell you where you are on a north-south line called a longitude.

” that run east to west across the globe, but tell you where you are on a north-south line called a longitude.

We also refer to latitude lines as parallels. In total, there are 180 degrees of latitude.

0° represents the equator, 90° represents the North Pole, and -90° represents the South Pole.

We can also examine the five significant parallels, which run from north to south: the Arctic Circle, the Tropic of Cancer, the Equator, the Tropic of Capricorn, and the Antarctic Circle.

Latitude has a bit of a “ladder” in it (with a bit of imagination), which may remind you that we measure latitude vertically.

In a grid reference, we usually state latitude first. For example:

34° 54.5′ S 143° 35.8′ E

4. What is meant by longitude?

Conversely, think of longitude as “lines” that run north to south across the globe but tell you where you are on an east-to-west line called a latitude. Lines of longitude are also called meridians.

Conversely, think of longitude as “lines” that run north to south across the globe but tell you where you are on an east-to-west line called a latitude. Lines of longitude are also called meridians.

There are 360 degrees of longitude, the centre of which is known as the Prime Meridian. It passes through the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, England. It divides our globe into the Eastern Hemisphere (west of 180 degrees of longitude) and the Western Hemisphere (east of 180 degrees of longitude).

Longitude is commonly stated last, for example.

34° 54.5′ S 143° 35.8′ E

5. Why do we use knots?

A knot is an old maritime measure of speed. If you cover one nautical mile in one hour, you will be travelling at a speed of one knot.

A knot is an old maritime measure of speed. If you cover one nautical mile in one hour, you will be travelling at a speed of one knot.

Knots are used in sailing as a unit of speed because they provide a standardised way of measuring and communicating a boat’s speed over water. The reason they’re preferred over miles per hour or kilometres per hour in maritime contexts comes down to history and practical application.

Here’s why:

Historical Context: The use of knots dates back to the 17th century, when sailors employed a device called a “log line” to measure their speed. The log line was a rope with knots tied at regular intervals. The rope was thrown overboard, and as the boat moved forward, the rope would unspool. By counting how many knots passed over the ship in a specific time frame (usually a measured time of 28 seconds), sailors could estimate the ship’s speed. That’s why speed became associated with “knots.”

Standardised Measurement: A knot is defined as one nautical mile per hour, and since nautical miles are based on the Earth’s geometry (1 minute of latitude equals 1 nautical mile), it’s very convenient for navigation. Using knots aligns with the use of latitude and longitude in navigation, making it easier for sailors to gauge distances and time during their voyages.

Ease of Communication: Knots are universally used by sailors, both for their convenience and for consistency across international waters. This consistency ensures that, regardless of your location, the concept of speed is understood in the same way, particularly when communicating with other vessels or using charts.

Navigational Precision: The use of knots is tied to how positions on Earth are measured, especially in terms of the nautical mile. Since a nautical mile is based on Earth’s circumference, this makes it more relevant and accurate for long-distance maritime navigation than using miles or kilometres, which don’t have the same direct relation to the Earth’s geometry.

So, it’s all about tradition, accuracy, and practical utility when navigating on the water!

For a better understanding, I recommend the movie Longitude, starring Stephen Fry as Sir Kenelm Digby and directed by Charles Sturridge. It is a great historical movie that explains the challenge of determining longitude within the British Navy.

If the article was helpful, feel free to share it on social media. If you find something that you think is incorrect, please don’t hesitate to let us know. We would love to hear from you, so leave a comment below.

Author

-

View all posts

View all postsRene is a keelboat instructor and sailing coach in the Mandurah area WA. He is also the author of several books about sailing including "The Book of Maritime Idioms" and "Renaming your boat".